[vLLM] PagedAttention: Saving Millions on Wasted GPU Memory

Performance · Code walkthrough of how vLLM applies virtual memory principles to unlock 24x throughput

LLM inference is frequently memory-bound - the GPU spends more time waiting for data than computing. The solution is batching: process 32 requests at once after reading model weights. But each request needs its own KV cache, and existing systems waste 60–80% of that memory due to fragmentation and over-reservation.

vLLM’s PagedAttention reduces this waste to under 4%, unlocking 24x higher throughput on the same hardware. For a 100-GPU cluster at $2/hour per GPU, eliminating this waste saves over a million dollars annually.

What is KV Cache?

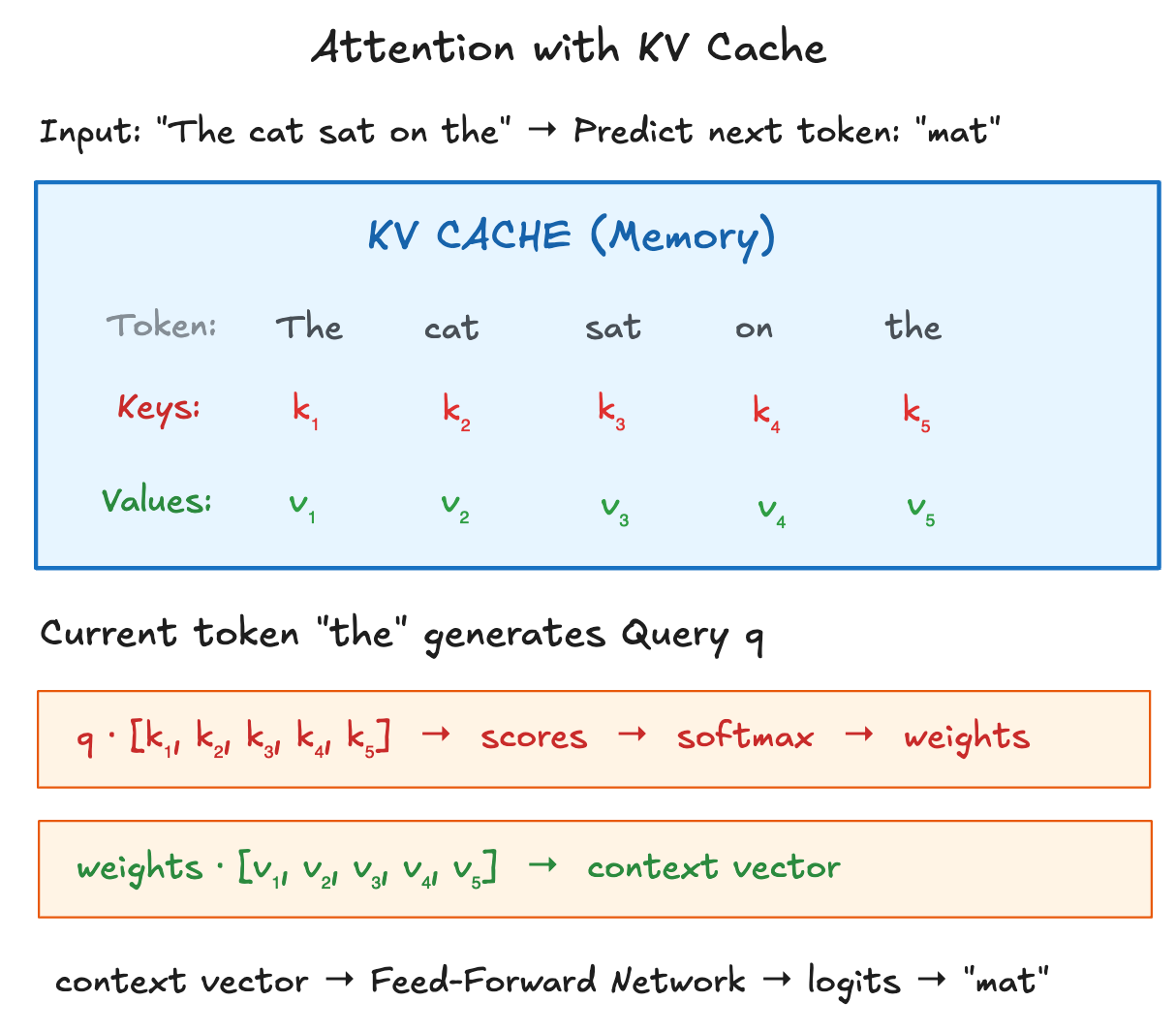

To generate Token #100, the model needs context from Tokens #1–99. Instead of recomputing this every time, it uses KV Cache, a searchable index.

The three vectors are

Query (Q): Generated from the latest token

Key (K): Cached from each past token, used to compute attention scores

Value (V): Cached from each past token, weighted by attention scores and summed to form the output

To predict token #100, the model retrieves cached Keys and Values for tokens #1–99 from GPU memory. The Query at position #99 computes attention scores against these Keys. Once token #100 is generated and fed back, its Key and Value are added to the cache.

The cache is larger than it might seem. The model computes K/V pairs at every attention head in every layer. For 99 tokens with 32 layers × 8 heads, Total KV pairs = 99 × 32 × 8 × 2 = 50,688 vectors. At 128 dimensions in fp16, this is around 13 MB per request. With higher number of tokens and greater batch size, memory fills fast.

Problem: Pre-allocation Waste

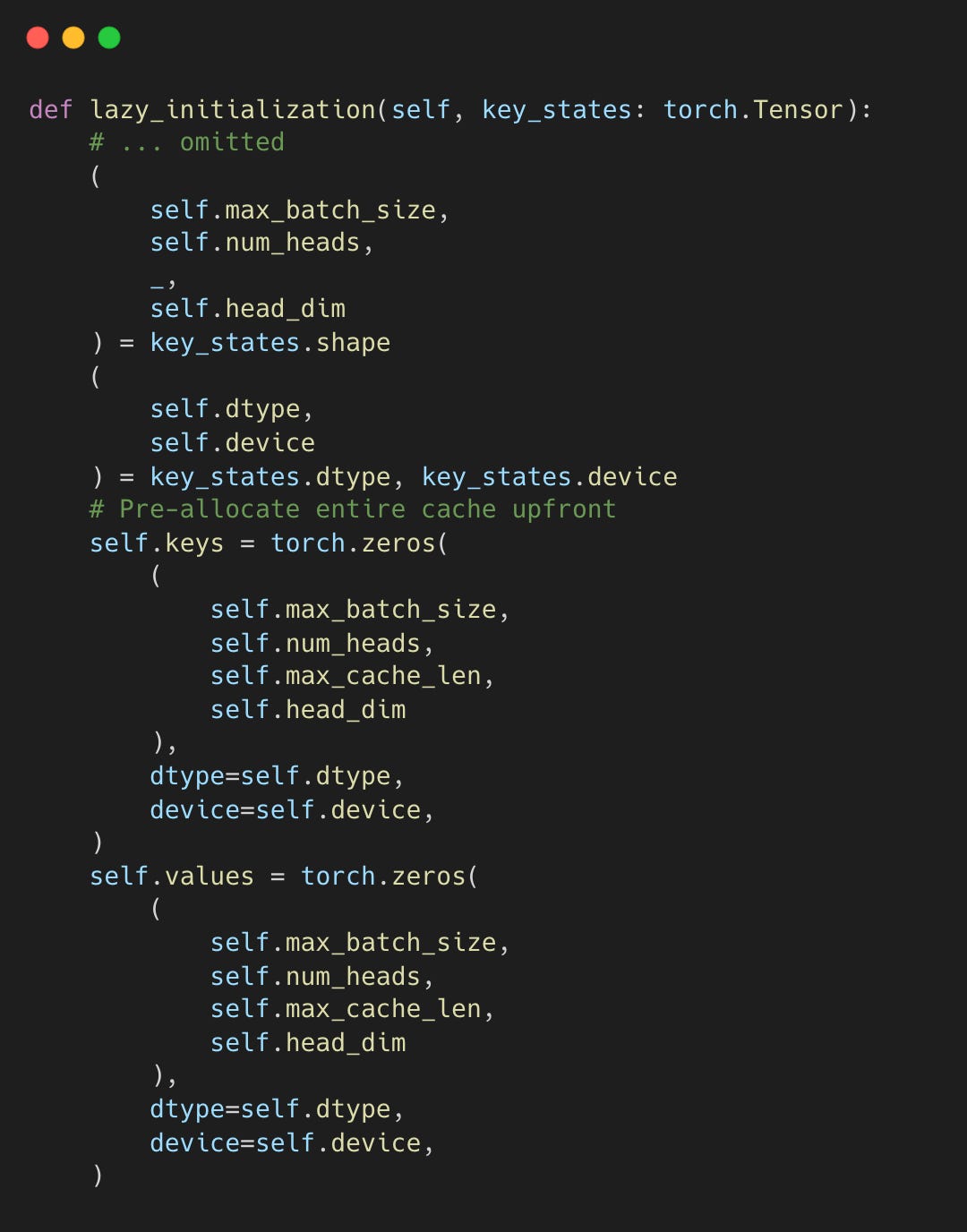

Traditional systems reserve contiguous memory for the maximum possible sequence (e.g., 2048 tokens) when a request starts. HuggingFace’s StaticCache pre-allocates tensors for the full max_cache_len.

huggingface/transformers:cache_utils.py#L265-L291

The entire max_cache_len is allocated regardless of actual usage. If a user generates only few tokens, the rest is wasted.

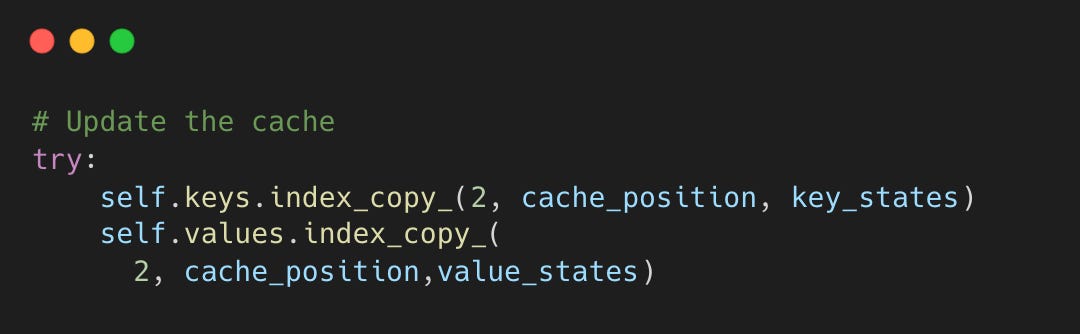

huggingface/transformers:cache_utils.py:L330-L333

When 60–80% of GPU memory sits idle, you can’t serve as many users. PagedAttention fixes this by breaking memory into small, flexible blocks.

Insight: Pages for KV Cache

The solution comes from a 1960s operating system innovation: virtual memory paging.

Physical RAM is limited, but programs want unlimited memory. The OS divides memory into fixed-size pages (typically 4KB). Each program sees a contiguous “virtual” address space, but the OS scatters pages across whatever physical RAM is available. A page table translates virtual addresses to physical locations. When RAM fills up, the OS evicts the least recently used page to disk. If the program accesses that page again, a page fault occurs and the OS swaps it back into RAM.

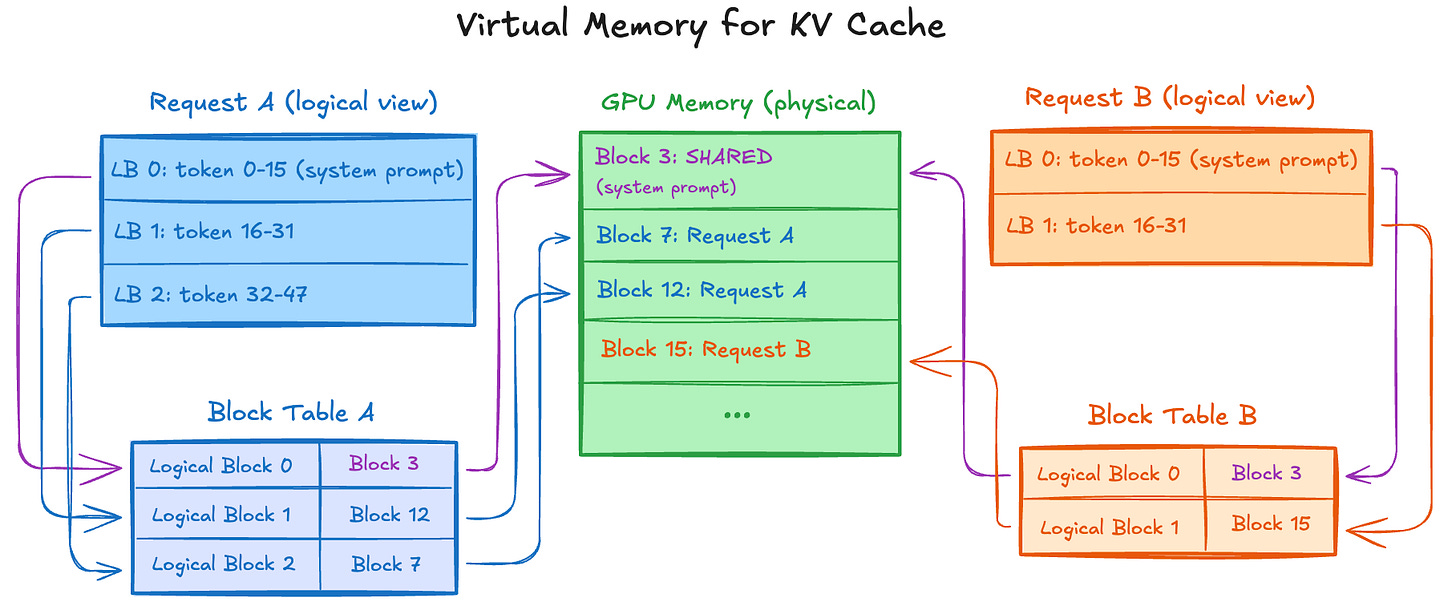

PagedAttention applies this to GPU memory. Instead of 4KB pages, it uses blocks of 16-32 tokens. Instead of virtual addresses, requests have logical block indices. Unused blocks return to a free pool managed by LRU.

Requests see contiguous logical blocks (LB 0, LB 1...) for tokens 0-15, 16-31...

Block Table maps each logical block → physical block (scattered in GPU memory)

Common prefixes (e.g., system prompts) share physical blocks via reference counting

When GPU memory is full → LRU eviction: least recently used block is recycled

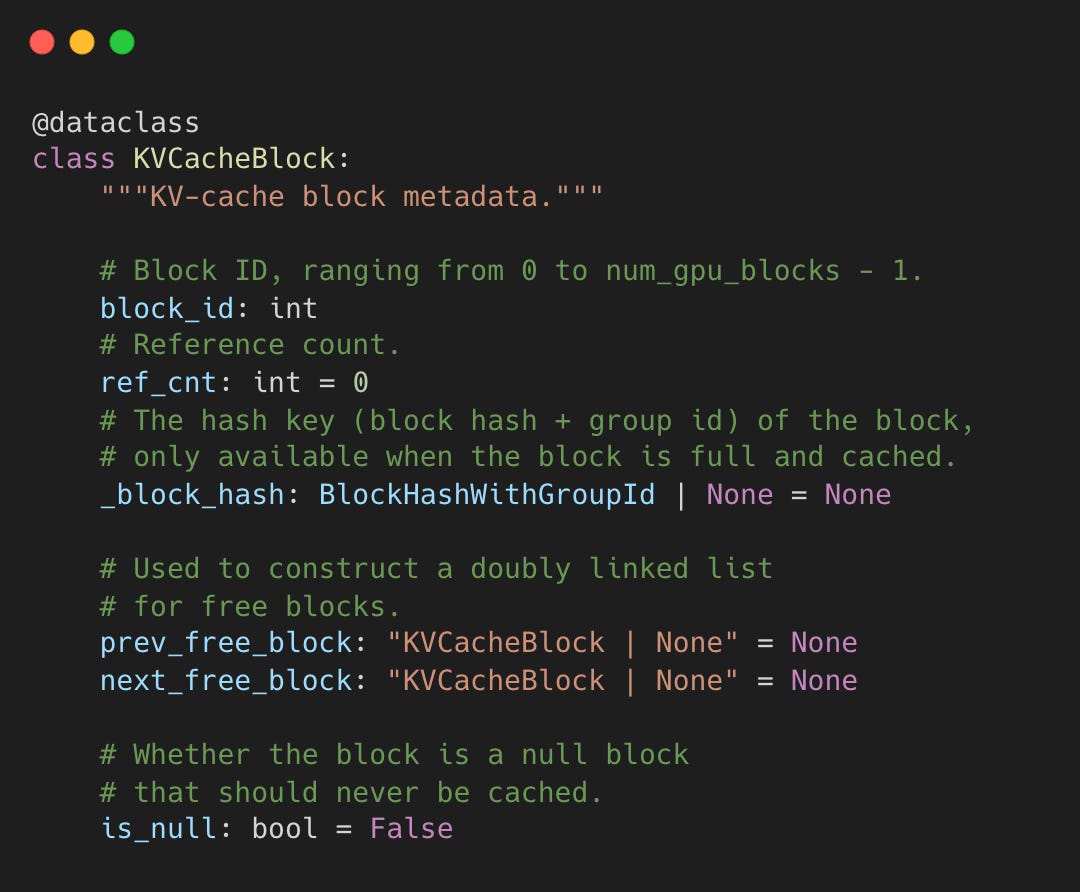

KVCacheBlock is the core data structure that makes it work.

vllm-project/vllm:kv_cache_utils.py#L107-L125

The prev_free_block and next_free_block pointers form a doubly-linked list enabling O(1) allocation and deallocation.

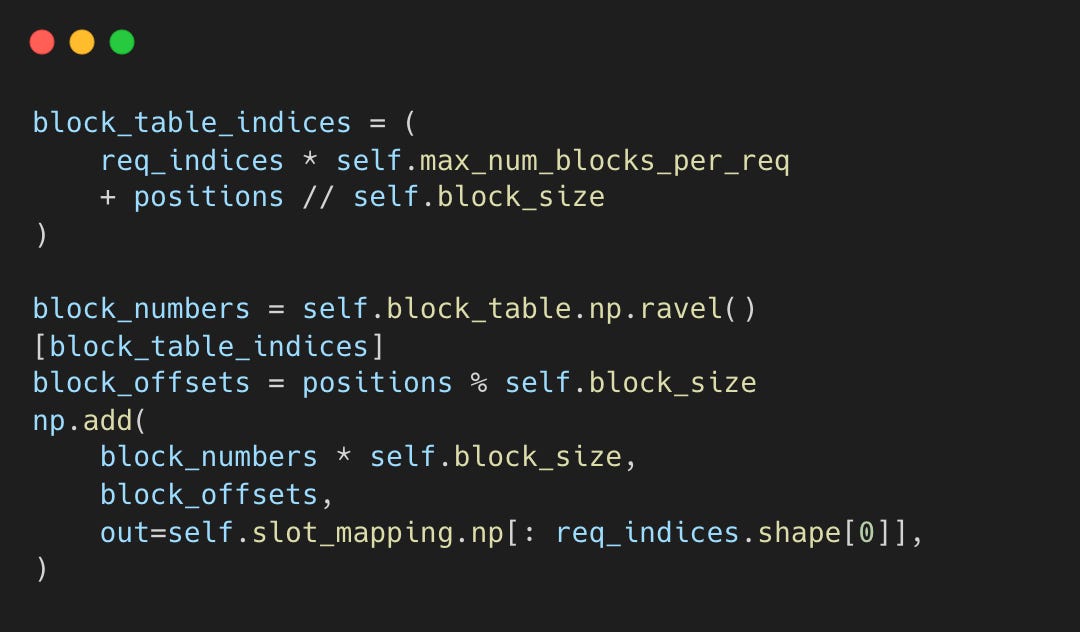

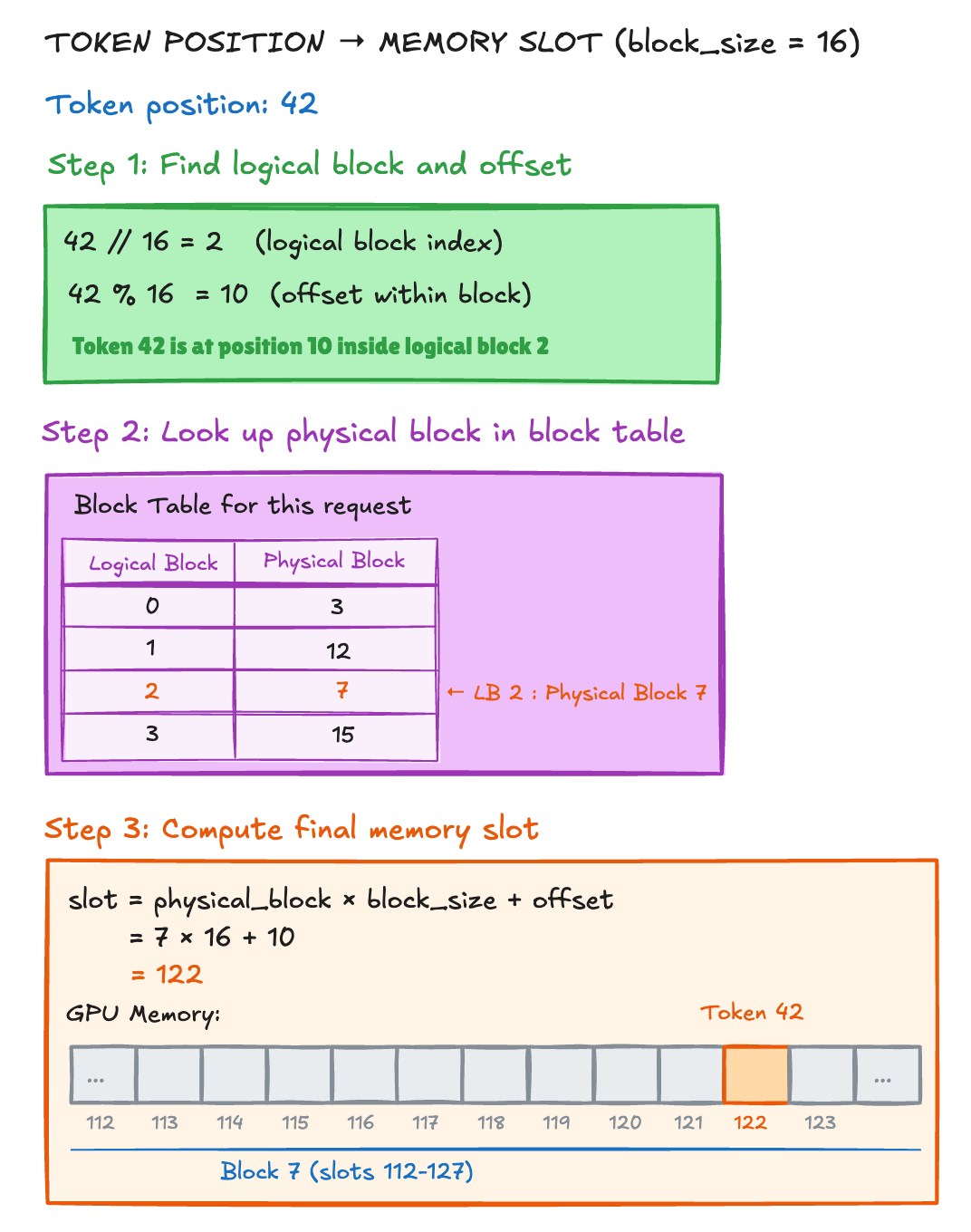

Mapping Tokens to Memory Slots

The block table translates token positions to memory locations:

vllm-project/vllm:block_table.py#L179-L190

Visualization of a concrete example:

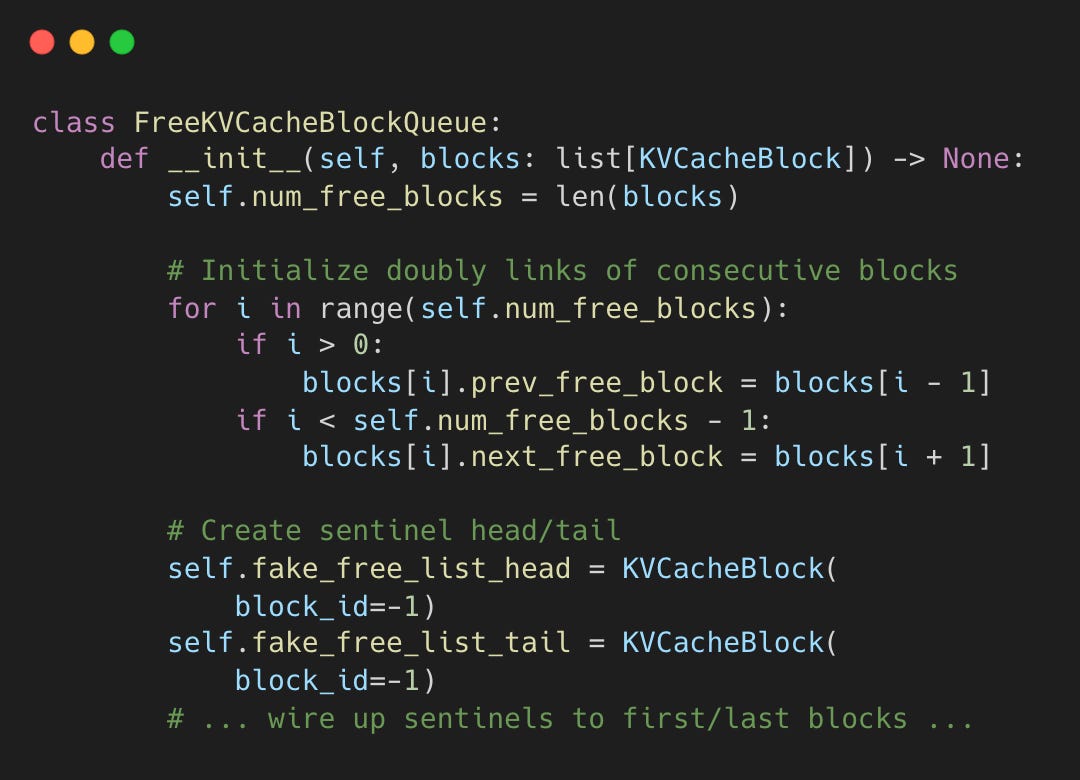

O(1) Block Management

vLLM’s FreeKVCacheBlockQueue uses a doubly-linked list with sentinel nodes for O(1) operations on all critical paths.

Initialization links blocks together, then attaches sentinel nodes at both ends (guaranteeing .prev and .next are never None, eliminating null checks).

vllm-project/vllm:kv_cache_utils.py#L156-L206

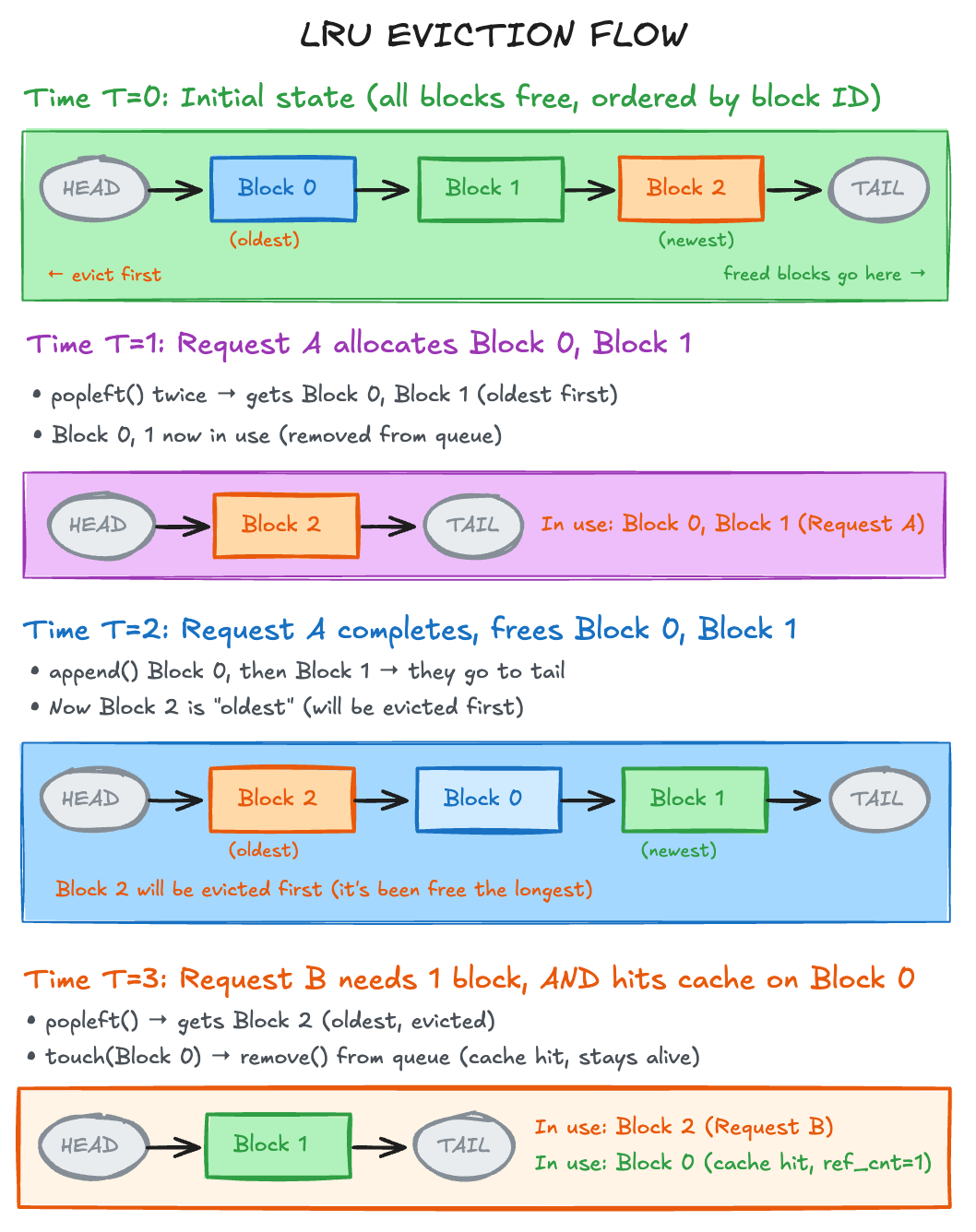

LRU (Least Recently Used) Implementation

The doubly-linked list maintains LRU (Least Recently Used) eviction order.

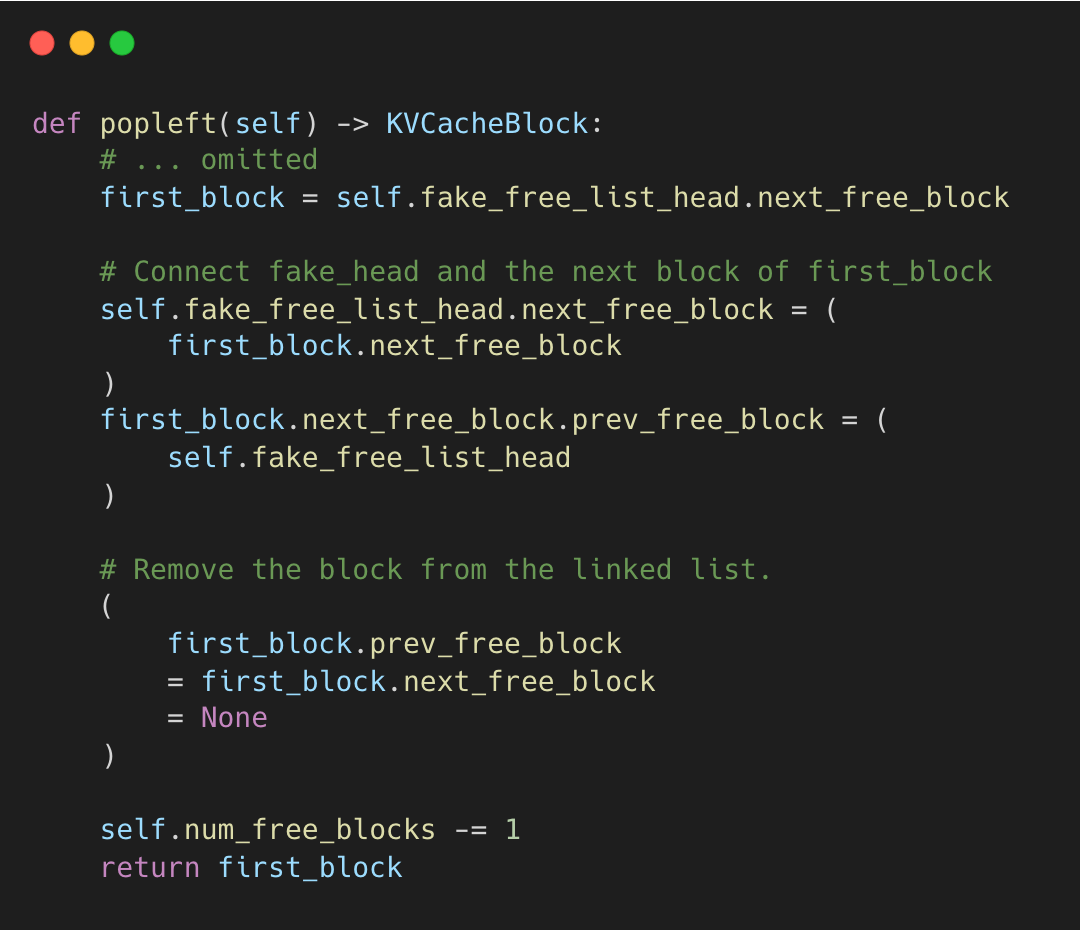

popleft() - grab a block from the head to use (the one that’s been free the longest)

vllm-project:kv_cache_utils.py#L208-L243

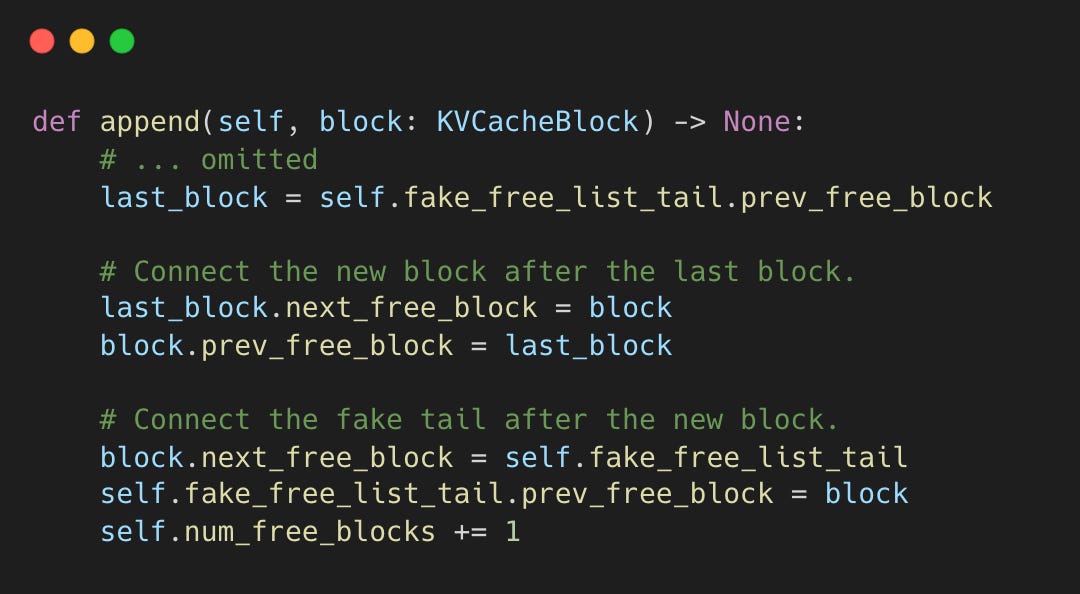

append() - return freed blocks to the tail (becomes most recently used)

vllm-project:kv_cache_utils.py#L298-L319

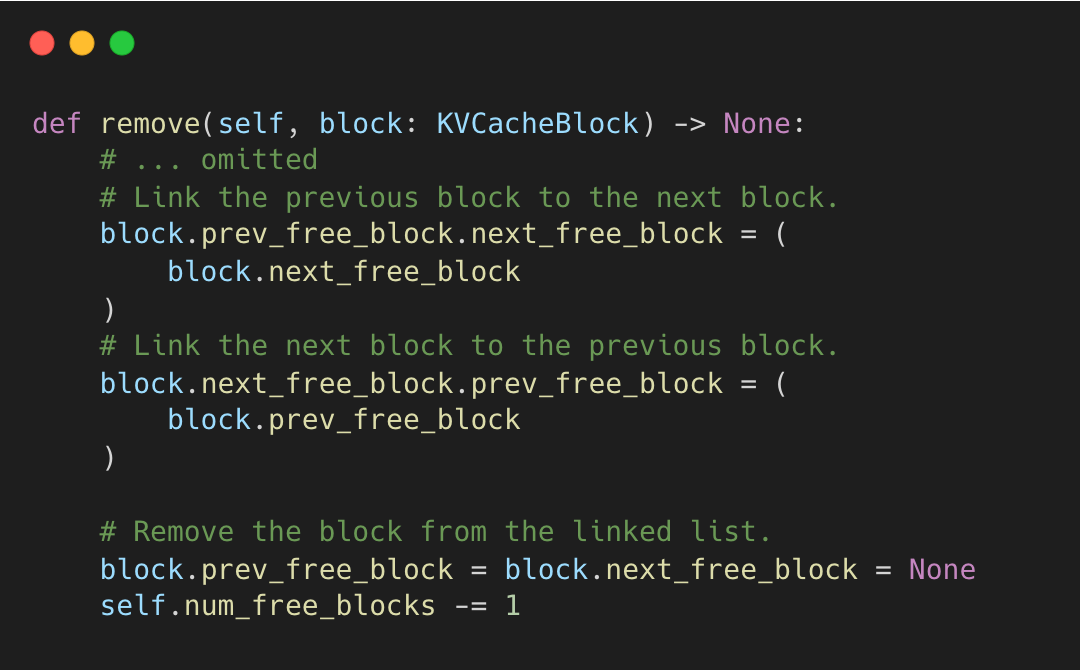

remove() - O(1) middle removal (for cache hits that should stay alive)

vllm-project:kv_cache_utils.py#L278-L296

Storing prev and next pointers directly in each KVCacheBlock (instead of using Python’s built-in list) avoids allocating wrapper objects, preventing garbage collection pauses during serving.

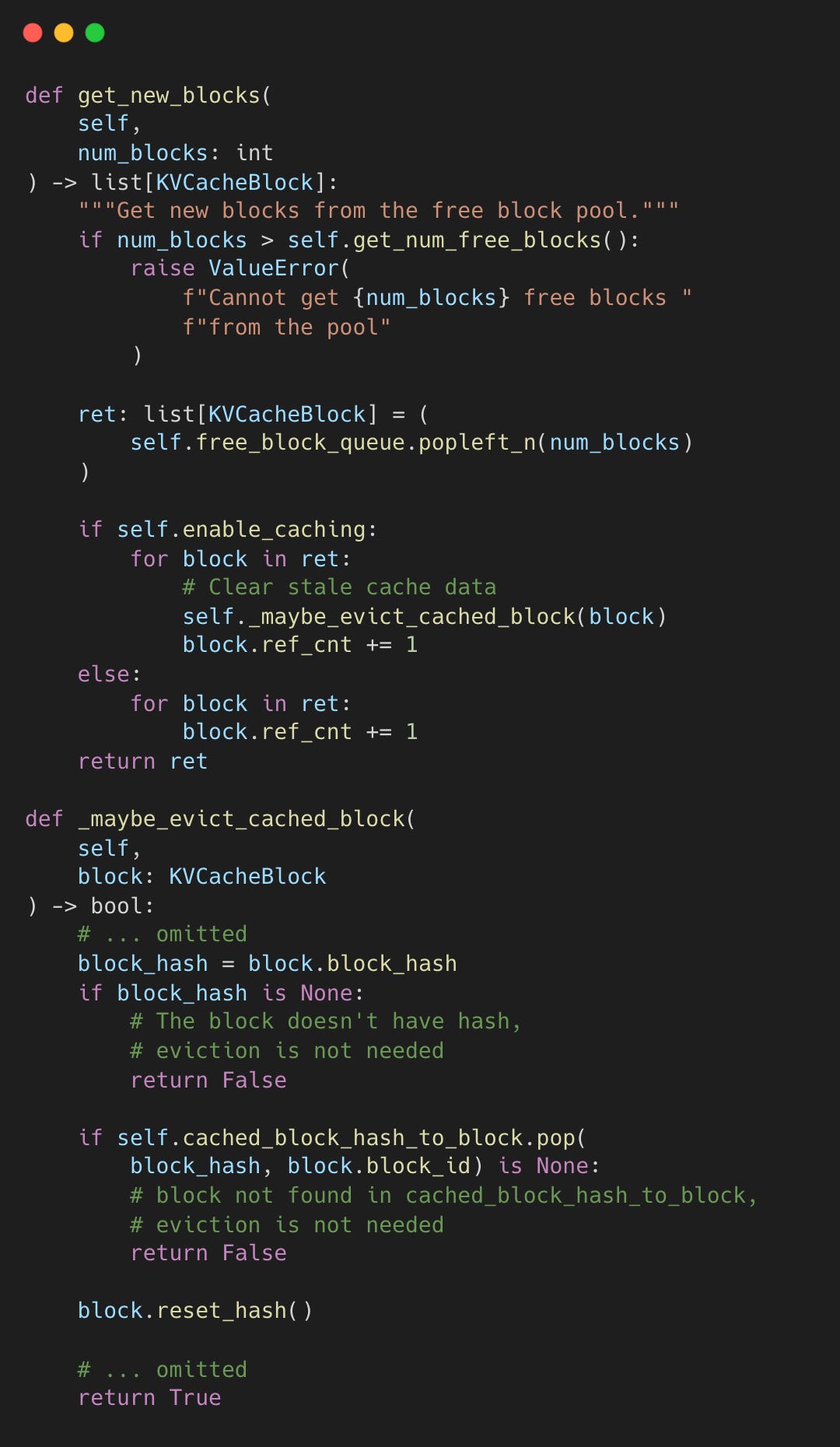

The BlockPool triggers eviction when allocating new blocks.

vllm-project/vllm:block_pool.py#L294-L364

popleft_n() pops blocks from the front (LRU order), then _maybe_evict_cached_block() clears cached hash data from the recycled block.

Efficient Block Sharing

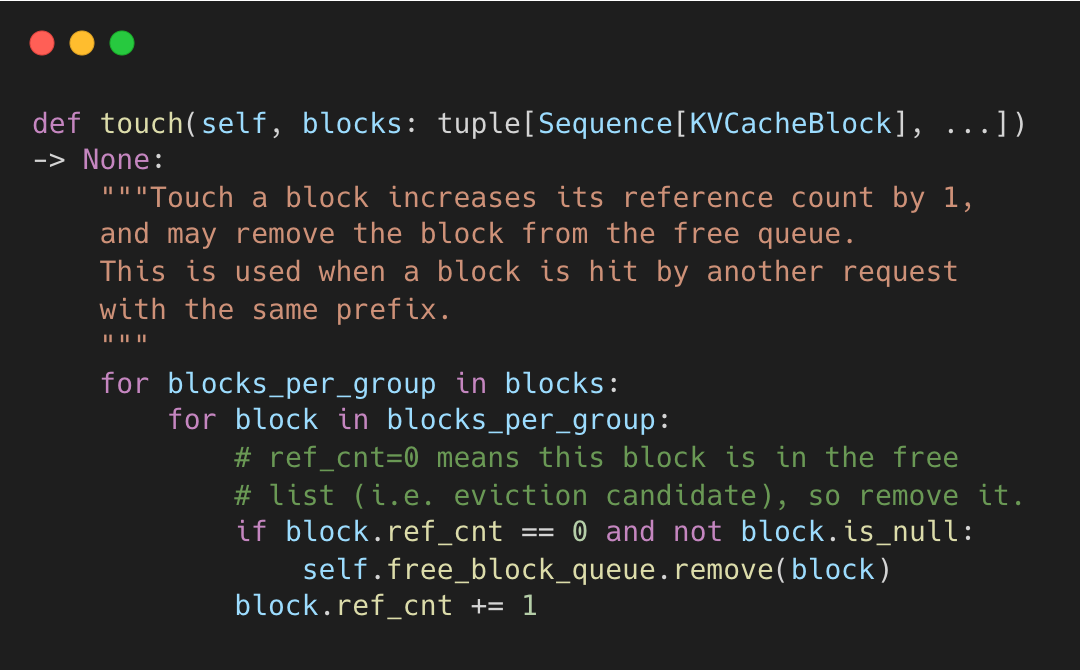

The ref_cnt field enables block sharing between requests. When a new request matches an existing prefix (common with system prompts), vLLM reuses the cached blocks instead of recomputing the KV cache. touch() increments the reference count to prevent eviction.

vllm-project/vllm:block_pool.py#L366-L382

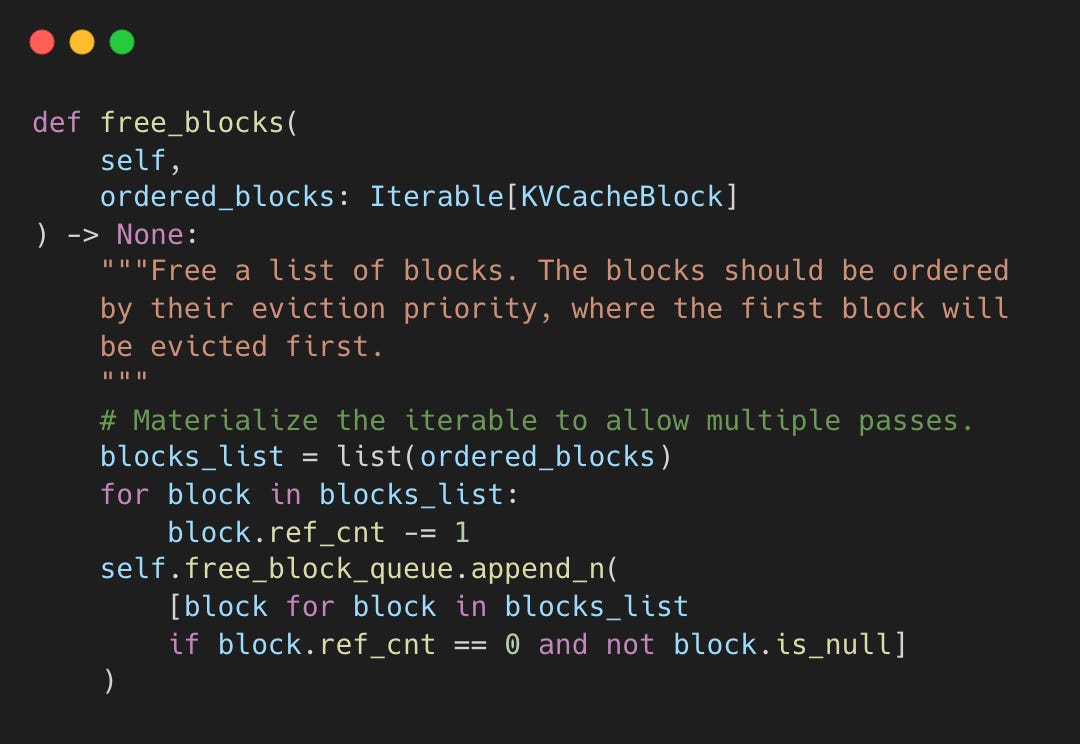

When a request finishes, blocks are freed by decrementing ref_cnt. Only when it hits zero does the block return to the free list.

vllm-project/vllm:block_pool.py#L384-L398

Freed blocks with ref_cnt == 0 retain their KV cache data and hash as eviction candidates. If a new request matches the prefix before eviction, touch() rescues it from the free queue. Data is only cleared when _maybe_evict_cached_block() runs during allocation to maximize reuse opportunity.

Using the Blocks in Attention

The block table drives two operations: writing new KV pairs to the cache, and reading cached KV pairs during attention.

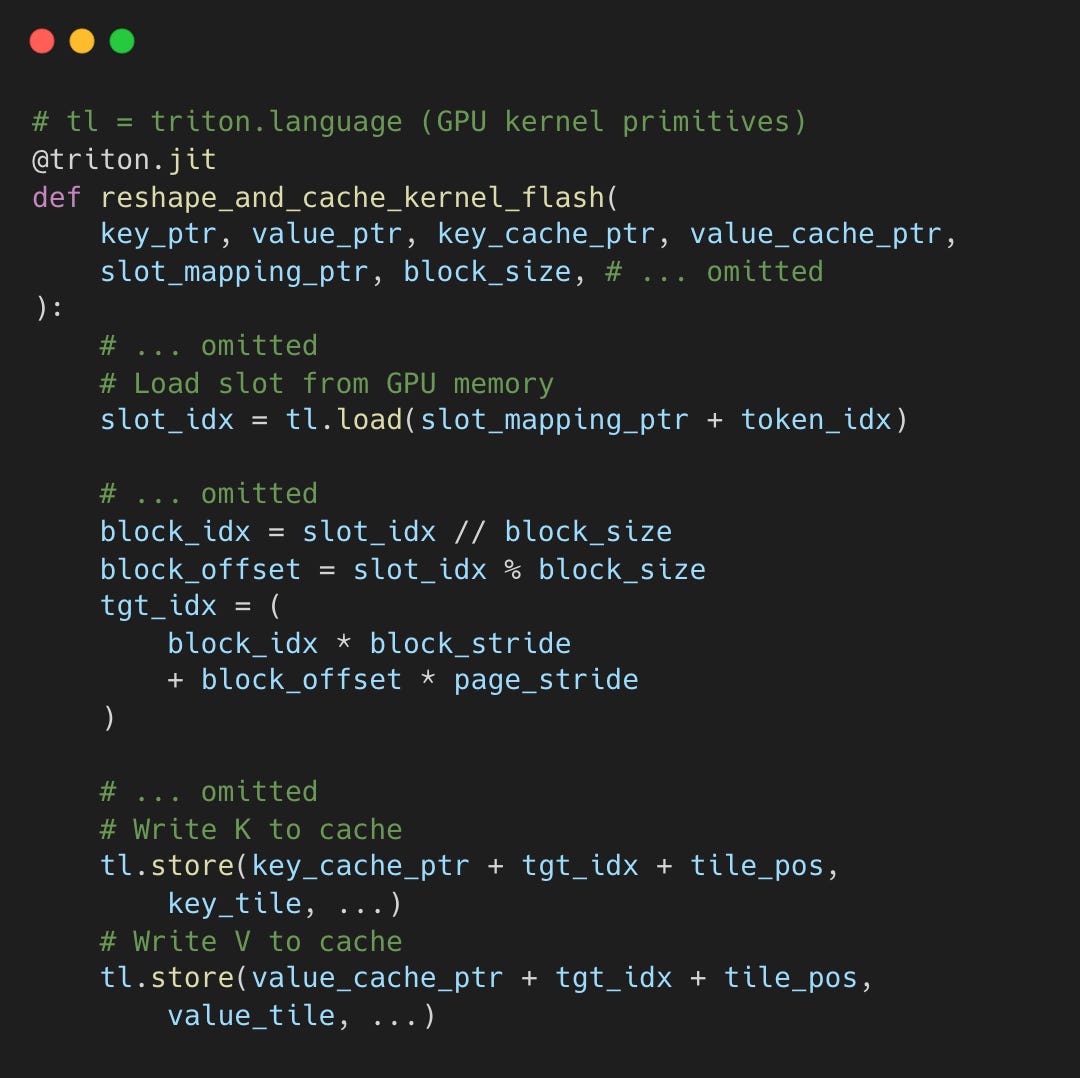

Writing to Cache

Each generated token’s KV pair is written using slot_mapping, per-token addresses computed from the block table. The kernel decomposes each slot into block index and offset.

vllm-project/vllm:triton_reshape_and_cache_flash.py#L10-L85

Reading during Attention

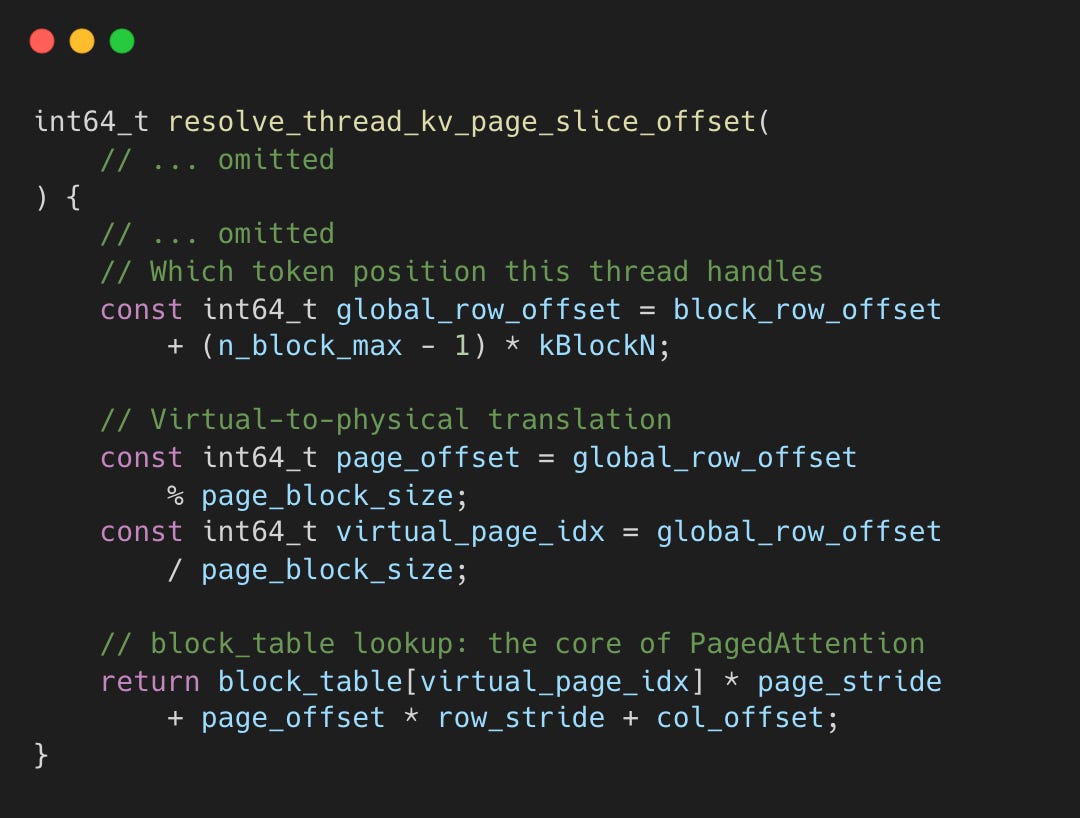

During attention, the kernel calls resolve_thread_kv_page_slice_offset to translate each thread’s token position into a physical cache address.

vllm-project/flash-attention:utils.h#L298-L314

The returned offset is added to the base K/V cache pointers, giving each GPU thread the exact memory address to load its assigned Key and Value vectors. The key line is block_table[virtual_page_idx] - this page table lookup is what allows physically scattered blocks to appear as a contiguous logical sequence during attention.

Design Choices

LRU eviction. The doubly-linked free queue maintains LRU order automatically - freed blocks append to the tail, allocations pop from the head.

Block granularity (16-32 tokens). Coarser granularity (entire sequences) would miss sharing opportunities. Finer granularity (individual tokens) would create too much bookkeeping overhead.

Reference counting. When ref_cnt hits zero, blocks return to the free pool immediately (no GC pause). They remain as eviction candidates with cached data intact until allocation recycles them.

Embedded list pointers. List pointers live in each KVCacheBlock, avoiding Python object allocation during list operations.

Major Contributions

SOSP 2023 Paper Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention by @WoosukKwon (Woosuk Kwon), @zhuohan123 (Zhuohan Li), and collaborators from UC Berkeley

Please let me know if I missed any other major contributors to PagedAttention!